Asset based community development: what's changed in 20 years?

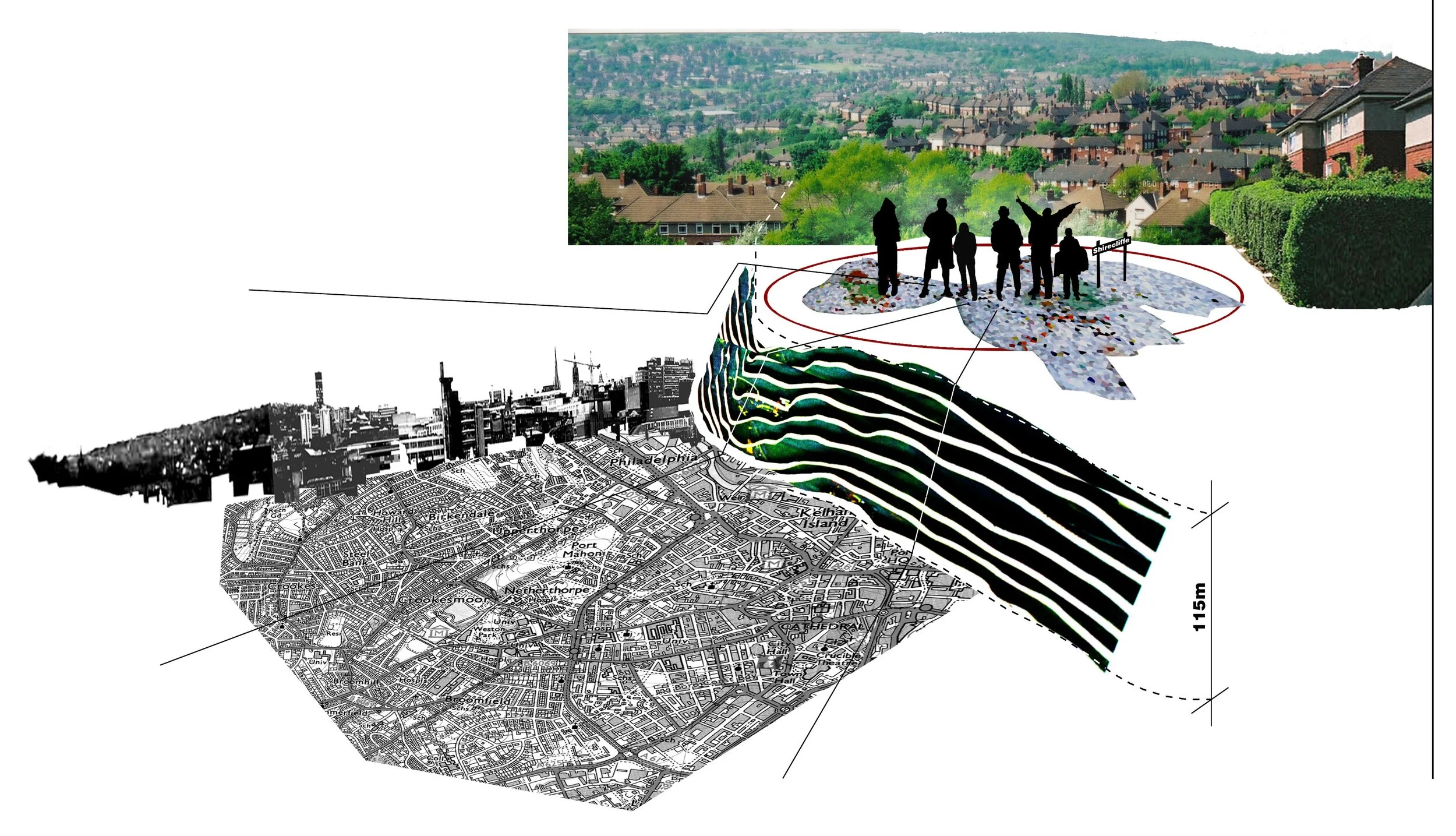

poster celebrating neighbourhoods in north sheffield: design by thomas matthews 2002

Looking back at SOAR’s Neighbourhood Strategies, a community-led neighbourhood planning process in north Sheffield

Project date 2000-2002

Team:

Southey Owlerton Area Regeneration (SOAR) (Board, Neighbourhood Forums and Theme Groups) - client

Chloe Aspinwall and Sarah Smith, from the SOAR team - facilitation and project management

Ian Smith, Ian Smith Associates - facilitator

Mike McCarthy & Clare McManus, Eventus - creative engagement

Prue Chiles and students from the University of Sheffield’s School of Architecture - design & communication

Andrew Grant, Grant Associates - design & landscape planning

At South Yorkshire Housing Association we want to start a conversation with our customers about the places they live in because:

#1 Covid-19 has highlighted the importance of community networks and well-designed homes, public spaces and gardens for people’s resilience and wellbeing.

#2 We are developing the design and sustainability standards for our new housing developments - and we want to apply the same ideas to our existing estates.

#3 The climate crisis means we all need to think differently about how to improve and manage our homes and green spaces.

#4 As stewards of these estates, we need a long-term plan for investment.

As with all work with our customers, we plan to take an asset-based approach.

We own and manage some 6,000 homes, spread across 50+ neighbourhoods in Sheffield City Region. Well Rotherham, our three-year public health programme in Waverley, is coming to an end, led by the talented Kris Mackay. It makes sense to learn from and build on the success of this asset-based approach to developing communities and improving health and wellbeing. We are testing out how it can work in two of our neighbourhoods.

But how do we scale up this approach to give us a picture of our whole estate? And how can we be confident that we can develop a plan that works for our customers in terms of their day-to-day experience, as well as for our business over a 20 or even 50-year horizon?

20 years ago, I led a planning process called ‘Neighbourhood Strategies’ in north Sheffield, which faced the same dilemma.

This blog describes:

What we did 20 years ago.

What worked then.

What will work even better today.

Neighbourhood Strategies in north Sheffield - how it started

In the first decade of the 21st century, a small experiment took place in north Sheffield: a group of us wanted to see if we could create a strategic and visionary masterplan for 6 neighbourhoods (50,000 population) starting not with facts and technical analysis, but with local people's stories and ideas.

Two things inspired this approach.

The first was a masterplan commissioned by Southey Owlerton Area Regeneration (SOAR).

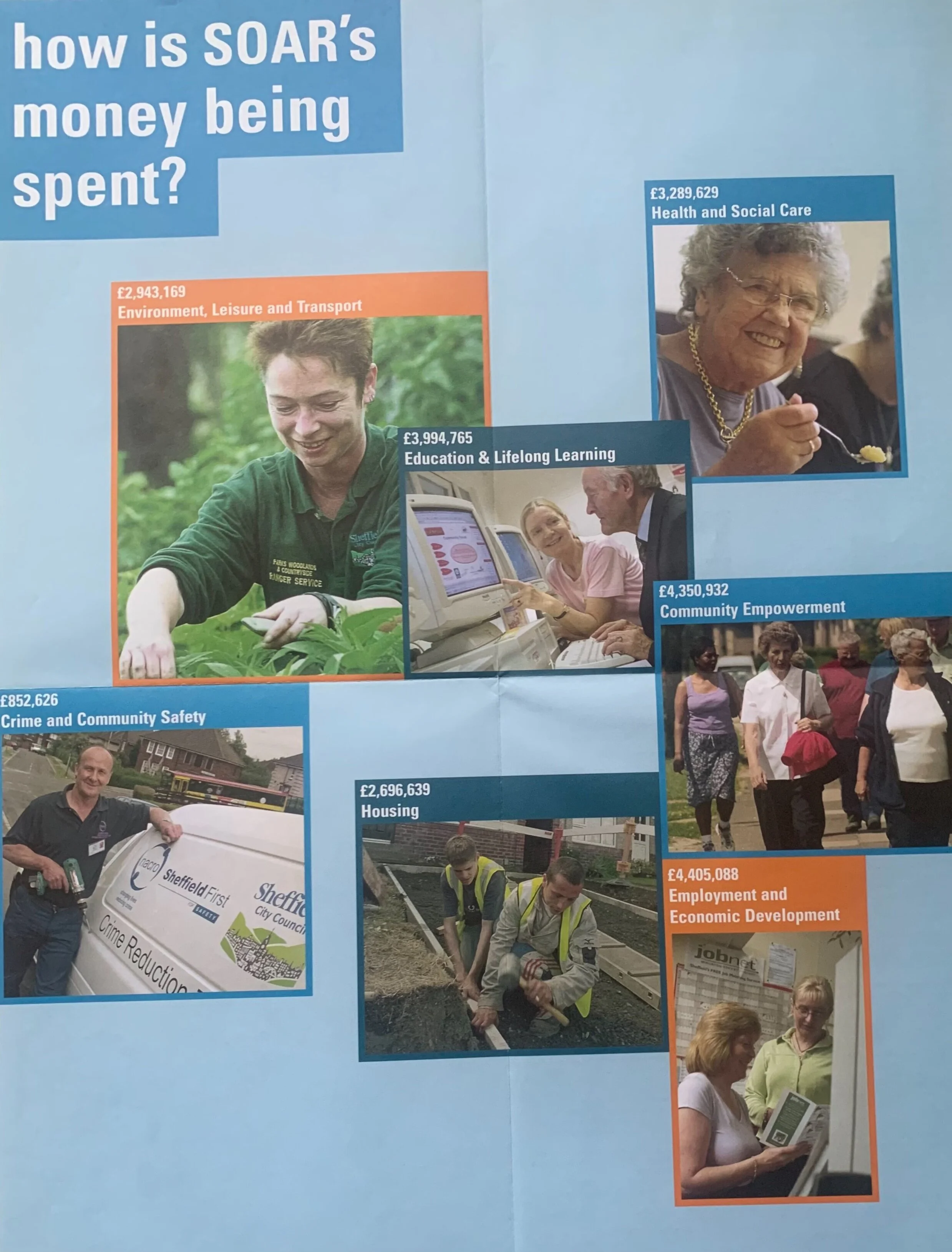

SOAR is a community-led partnership that was awarded £25m of government and European funding in 1999 for a 7-year programme. Comprising 20,000 households and a tenth of the city’s population it was one of the most deprived parts of the UK and Europe’s largest council estate. SOAR’s first project was to commission a masterplan to guide future investment across the area.

southey owlerton is an inter-war housing estate in north sheffield

the area is green, hilly and has spectacular views

The masterplan was developed by consultants and poorly received locally, mainly because it recommended widespread demolition of council housing in three of the six neighbourhoods. But there were other difficulties with the plan: it contained diagrammatic, broad brush proposals that lacked detail at the neighbourhood level; it was text heavy with few images which made it hard to communicate the ideas; and most importantly, local people had not led the process which generated the plan.

The SOAR Board rejected it and commissioned a new and different process: one that was led by local people at a neighbourhood level, that was visual in communicating ideas and that invited professionals with specific expertise to join a team of residents and council employees, rather than handing the whole process over to a team of consultants. This process became known as the Neighbourhood Strategies.

The second source of inspiration was Franco Bianchini's ideas on the role of creativity in the successful development of a city, as set out in The Creative City, a Demos report (1995/6). Bianchini argues that new tools and techniques in city development are needed to address the issues that cities face today.

In the 19th century, the particular creativity of engineers, planners and scientists was needed to tackle physical infrastructure for sewage, transport and rapid housing development. They used rational, analytical thinking grounded in science and logic. In the 20th century planners continued to interpret social problems in physical terms and use analytical tools.

Today there is a recognition that cities need to embrace social, environmental and economic issues and to do this, they will need new tools that make connections between problems, rather than separating them into boxes, that open up new ways of looking at issues and that respond to the personal, the local and the everyday as well as the strategic and visionary.

Ideas about creativity in planning city neighbourhoods influenced the process in a number of ways…

New ways of working - local people were at the centre of a partnership with the council, other agencies, professionals and city-wide institutions; the council team included representatives from each directorate so that we could make connections between issues - this sounds obvious but was radical at the time and won the council its first national award (The Municipal Journal Local Government Social Inclusion Achievement Award 2004).

New ways of talking - artists and facilitators opened up a dialogue between local people and professionals; walkabouts, games and events were used to generate and test ideas and themes; ideas were presented as collages, loose proposals open to interpretation, not designs but images, to provoke conversations.

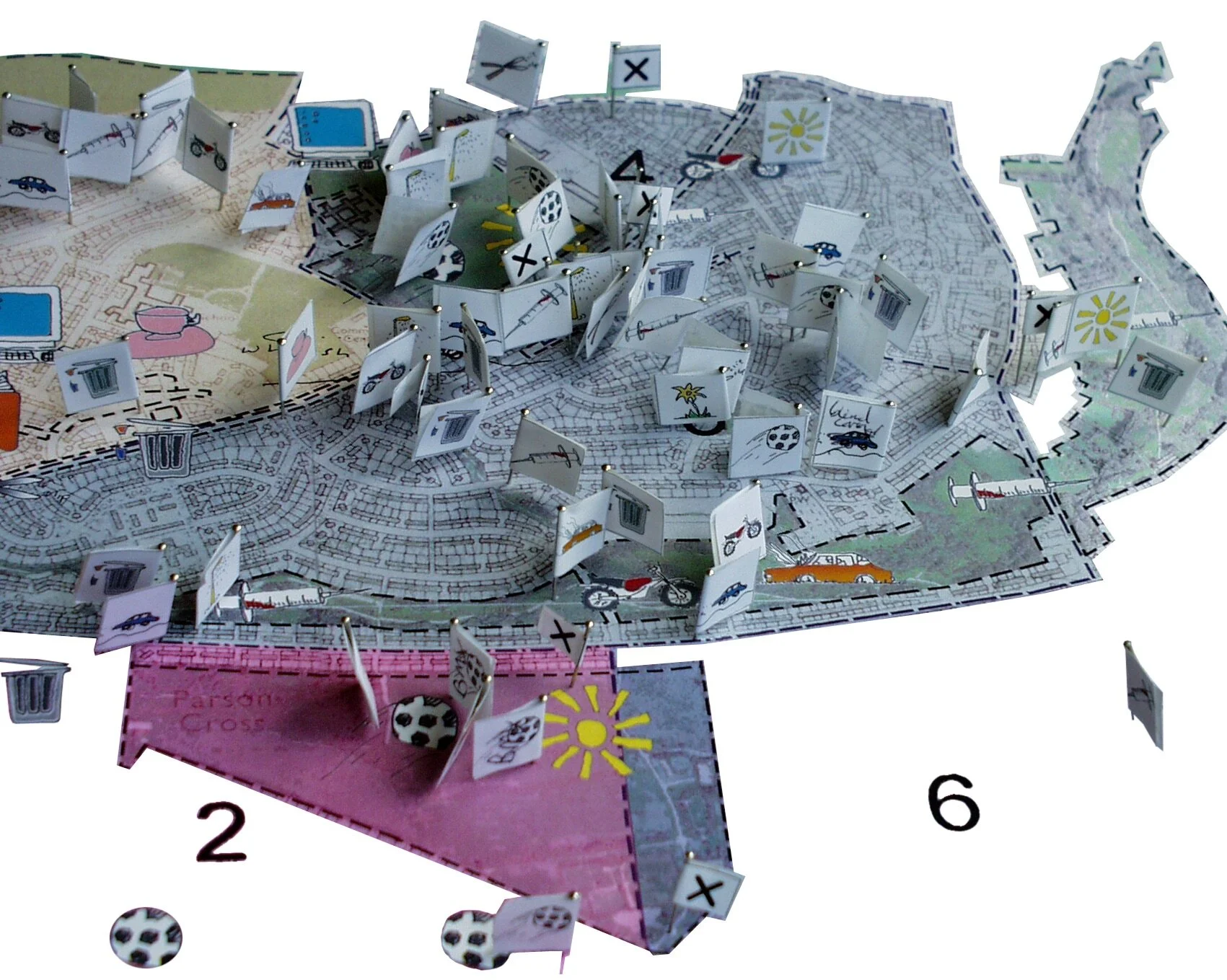

New ways of mapping - the starting point was what local people told us about their neighbourhood, not a technical analysis; information derived from stories, such as a favourite walk or view, was recorded and used to investigate and draw out themes that would have been missed by conventional reports; each neighbourhood worked from a 3D model.

The SOAR partnership

aerial view of southey owlerton

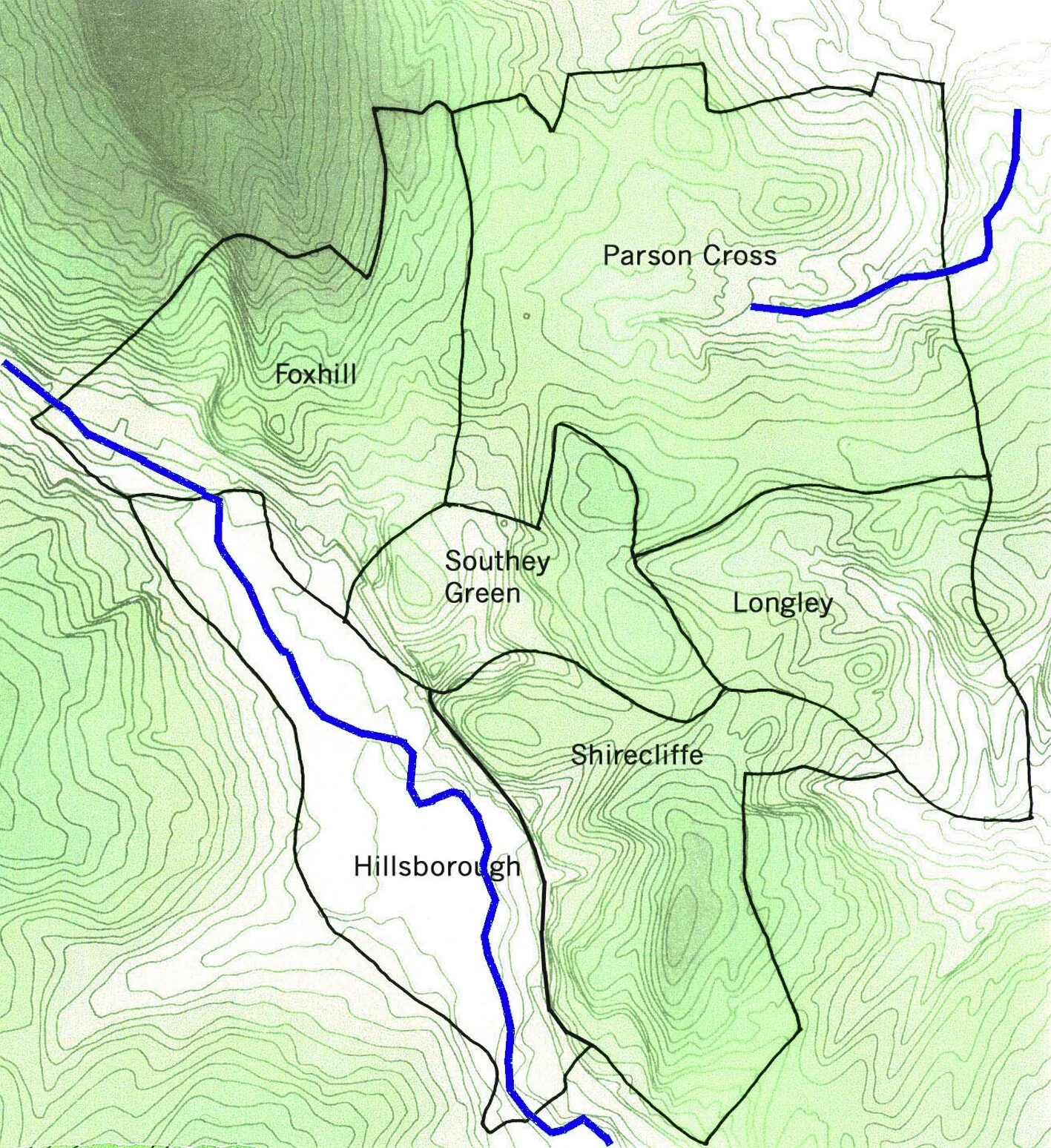

The SOAR area comprises 6 neighbourhoods: Foxhill, Longley, old and new Parson Cross, Shirecliffe and Southey. The area is a product of Abercrombie's 1924 plan for Sheffield which proposed satellite suburbs or communities to be developed on garden city principles on areas of former countryside. Plans for 2000 homes at Longley were approved in 1926 and the programme continued into the 1950s across Southey Owlerton, totalling some 20,000 homes in all.

By 2000 the area was in decline. The Council prioritised the area for its bid for Single Regeneration Budget Round 5 and Objective 1 ERDF, based on evidence of multiple deprivation and lobbying by local people. The funding supported social, environmental and economic activity to develop more sustainable communities. The first priorities were to form a partnership and agree a plan to guide the investment.

We didn’t talk about co-production back then, but that is how the partnership worked: the programme was co-governed, co-designed, co-commissioned, co-delivered and co-evaluated.

poster of the soar programme: design thomas matthews 2002

Local people worked on the funding bids and had equal representation on the Partnership Board and on the six theme groups that allocated the funding.

Following a governance review part way through the programme, each neighbourhood elected two representatives to the Board, through democratic elections run via the electoral roll, to sit alongside council members and agency partners. A local person chaired the SOAR Board and co-chaired each theme group.

Residents decided what to fund, wrote the briefs for the projects and selected and managed the professionals who would support them to deliver.

Local people, supported by New Economics Foundation, led the interim evaluation of the programme which resulted in a more equitable split of investment across neighbourhoods and shifted the funding to match their priorities. At the time this was ground-breaking: every other regeneration partnership in the city hired consultants to undertake their interim evaluation.

And so, when it came to designing the plans for the area, it was essential and obvious to SOAR, that local people would lead the process.

The Council was nervous. It wanted to see a strategic plan for the area and it worried that the people who lived there would come up with a set of grass roots proposals that worked for them, but lacked impact at a city scale.

The process took six months to agree. It was piloted in one neighbourhood over six months, and then rolled out to the other five neighbourhoods in sequence over the following 12 months. After two years of working in this way, we collectively produced six neighbourhood plans and an overarching regeneration framework that knitted the six plans together into a vision for the area.

The Council and Sheffield’s Local Strategic Partnership endorsed the plans and adopted them as the strategy for the area, commenting that it was extraordinary that the plans were both strategic and rooted in local people’s ideas. 20 years later they are still in force.

How did we achieve this?

#1 Twin experts

there were a lot of events in tents! actually there were a lot of other events and meetings, but we only ever photographed the ones in tents.

Local people’s experience of living in a place was the starting point: and their expertise in their neighbourhood was valued equally with professional expertise, in what we called the “twin experts” approach. Their collaboration drove the end result.

The core group for each neighbourhood comprised people who lived there, as well as local councillors and project partners. They tended to be people who were active in their Tenants and Residents Associations, or in grass roots community work in their neighbourhood.

A multidisciplinary team of council/agency employees and a small band of consultants that we invited into the process, supported the neighbourhood group at each stage, reviewing the outcome of each activity and preparing the materials for the next part of the conversation.

Small grants kickstarted the process: each neighbourhood group was awarded £10k of funding to develop its plan, including micro grants to support grass roots projects. The process was led throughout by local people.

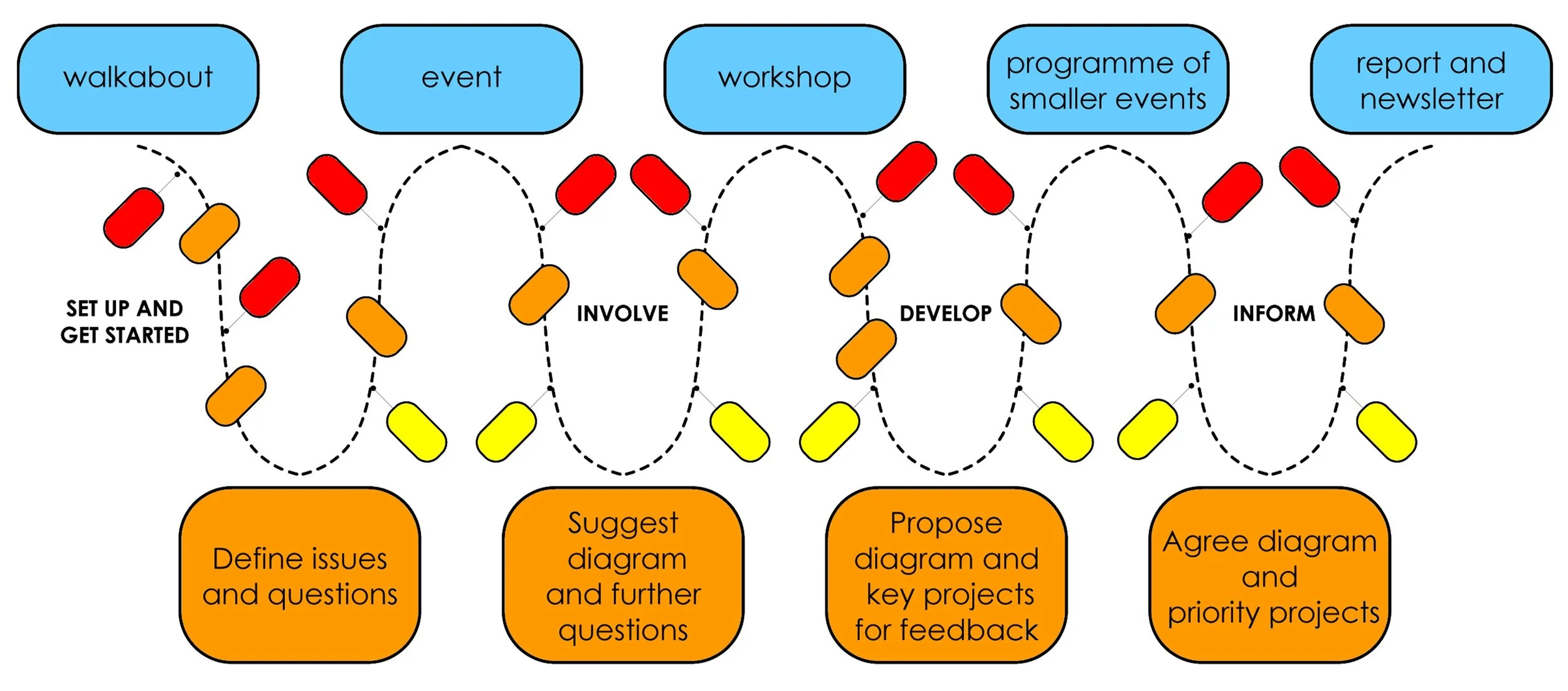

The process always started with a walkabout for local people to introduce the professional team to the area, its strengths and opportunities for improvement. data is great, but there’s nothing like getting out into a place. Walking and talking was also a great way to get to know each other.

a “big tent event” allowed the core neighbourhood group to talk to the wider community about the issues and opportunities, using artists and creative tools to open up conversations.

a wall of postcards created by residents at parson cross festival describing what they appreciated about their neighbourhood and how it could be better.

Workshops and smaller events followed and allowed stakeholders to work through specific ideas and give feedback on the emerging proposals.

Through a series of conversations over numerous smaller meetings, we honed the plans.

The results were written up in a short, visual, easy-to-read report for each neighbourhood. The report was signed off by the neighbourhood group and shared via a local newsletter.

The process was a dialogue between the two teams of experts, iterative and collaborative. The issues and questions explored in all the events reflected the perspectives of all the key players. We were able to describe a generic process that looks coherent in this diagram, but in practice, it was different in each neighbourhood and felt messy and complicated most of the time!

#2 Excellent listeners, thinkers & designers

We knew we needed facilitation, design thinking and creativity to build trust with the community and translate their ideas into compelling plans. And after the difficulty with the first masterplan, where the process had been handed over to consultants, it was important that we brought in consultants who would support rather than lead.

We needed people who were excellent thinkers and designers and excellent at working with the community.

prue chiles (right) with input from students from the university of sheffield’s school of architecture brought design ideas and communication tools.

ian smith helped with the facilitation.

andrew grant (left) generated the overall Framework for the place. mike mccarthy (second left) and clare mcmanus (right) from eventus brought creative engagement techniques.

This team was brilliant at listening and soaking up through conversations and events what mattered to local people and what it was like to live there. This was the foundation for the ideas and proposals.

However tempting it was to revert to conventional practice, the professional team held onto the principle of starting with people's personal accounts of the area. For example, in one neighbourhood, people on the walkabout and at later events talked frequently of the views and how memorable and important they were.

Views are a key theme in a city built on hills. But when we came to do the technical topographical analysis, we discovered that this neighbourhood had a particularly "knotty" landform that meant that the views were constantly changing and surprising at every turn: people's observations highlighted a special feature that we might otherwise have missed.

#3 Creative tools & visual techniques

Creative tools were chosen to reveal and highlight issues. Following the unhappy experience with the first master plan it was important to open up dialogue and build trust between the different participants. And creative tools are a great leveller!

The aim of the process was to arrive at an agreed diagram or “game plan” for the neighbourhood that identified the key projects or changes that were needed, physical and non-physical, as well as some thoughts about the overall identity of the neighbourhood.

ribbons on a map capture movement patterns in a neighbourhood.

the knotty landform creates the constantly changing views that are a key feature of the area.

At Parson Cross festival, hundreds of people completed postcards about what they liked and wanted to see change in their neighbourhood, using drawing, collage and words.

Other activities captured movement patterns and ideas for improvements. A time-line photo activity explored people’s personal experiences of living in the area.

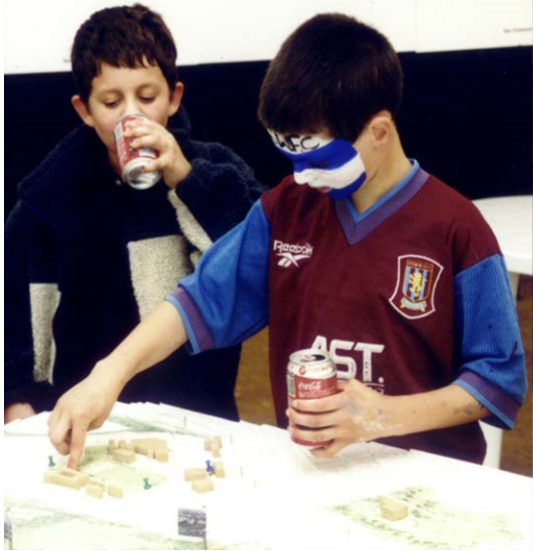

People marked their homes and suggestions on 3-D models of each neighbourhood built up from contour plans.

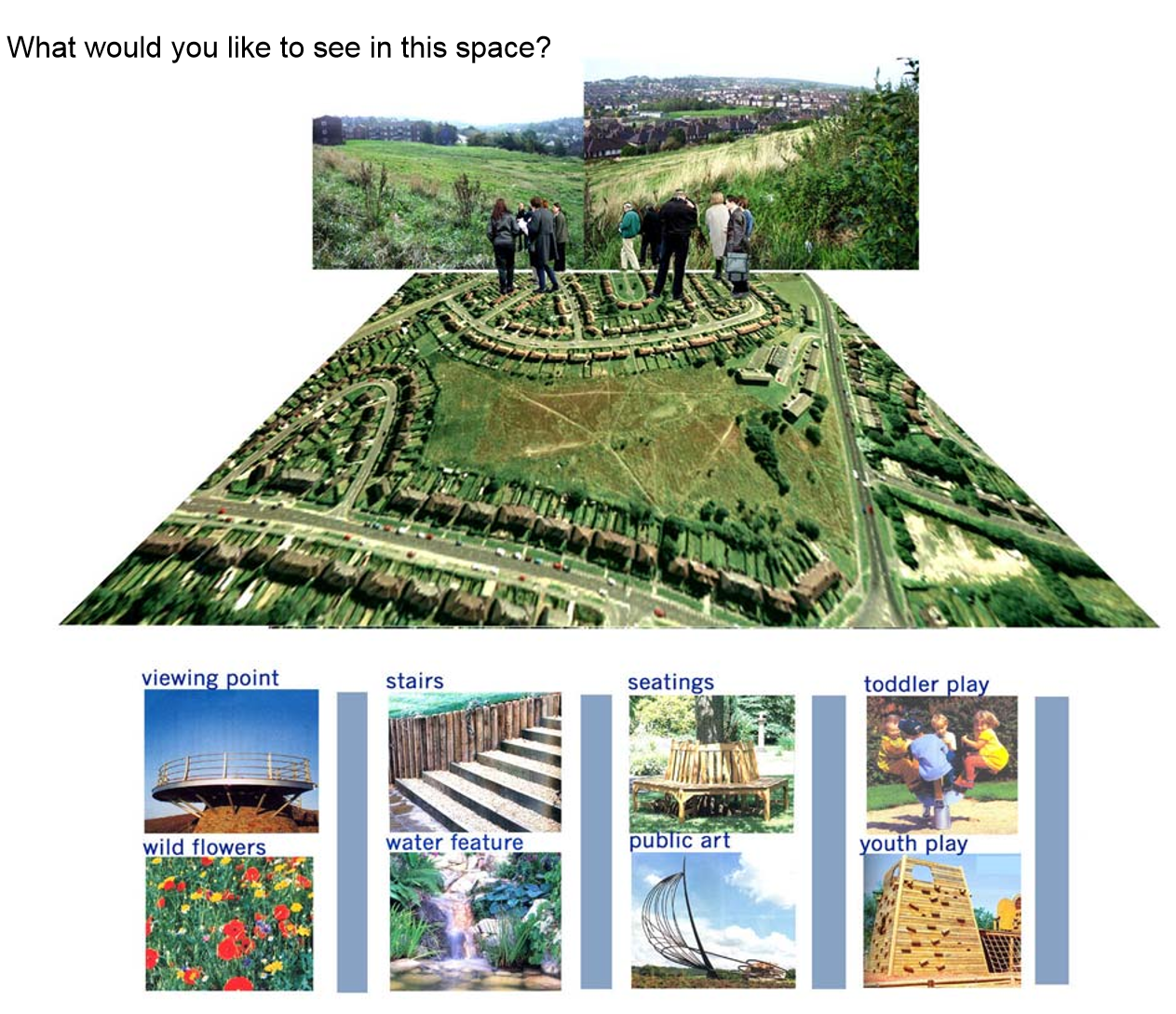

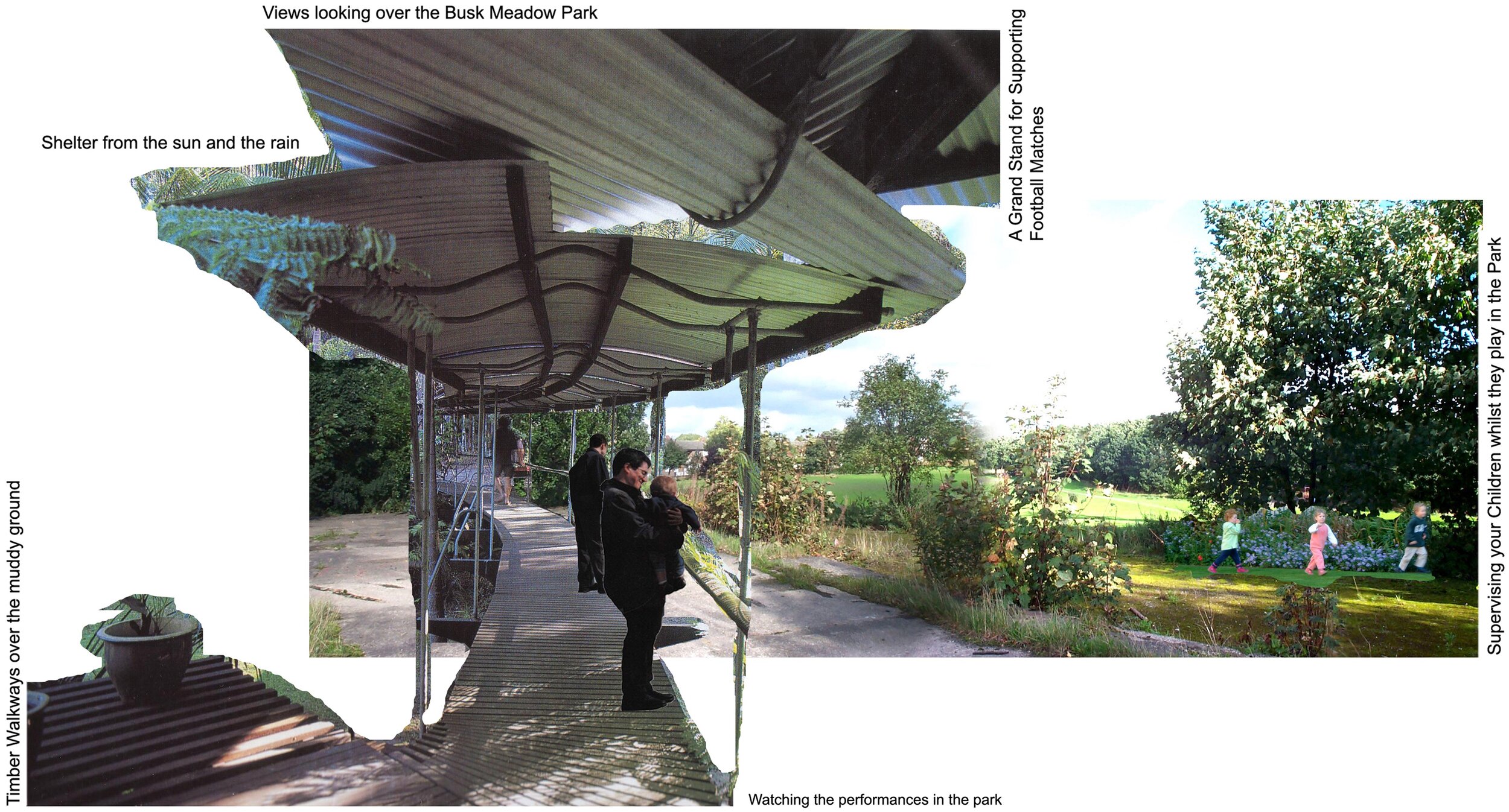

“Trigger boards” which showed ideas, rather than proposals, were used to stimulate debate.

We used diagrams to communicate the plans for each neighbourhood to select and highlight key interventions, rather than getting lost in mapping all the issues and activities. Diagrams are also less likely to date. I am a big fan of diagrams.

We used a common notation for the diagrams based on the themes we had heard across all the neighbourhoods. The individual diagrams stitched together into a framework for the area as a whole.

If you stand back from the detail of the framework diagram some overarching “big ideas” emerged. These celebrated The area’s special characteristics and history - in this case, the gritstone edgeS that run thRough It - and helped connect the area to the rest of the city and the peak district beyond.

Park city has been adopted more widely across the city - Sheffield is known up and down the country for the extent and quality of its green spaces, andrew grant drew these diagrams with felt pen and first presented them to us on an overhead projector - remember them?

Collages and drawings were used to describe the identity of the area and suggest how it could evolve.

The concepts of the (community owned) hub building and “community high street” became key elements of the regeneration plans alongside parks and new housing.

#4 Working at different spatial scales

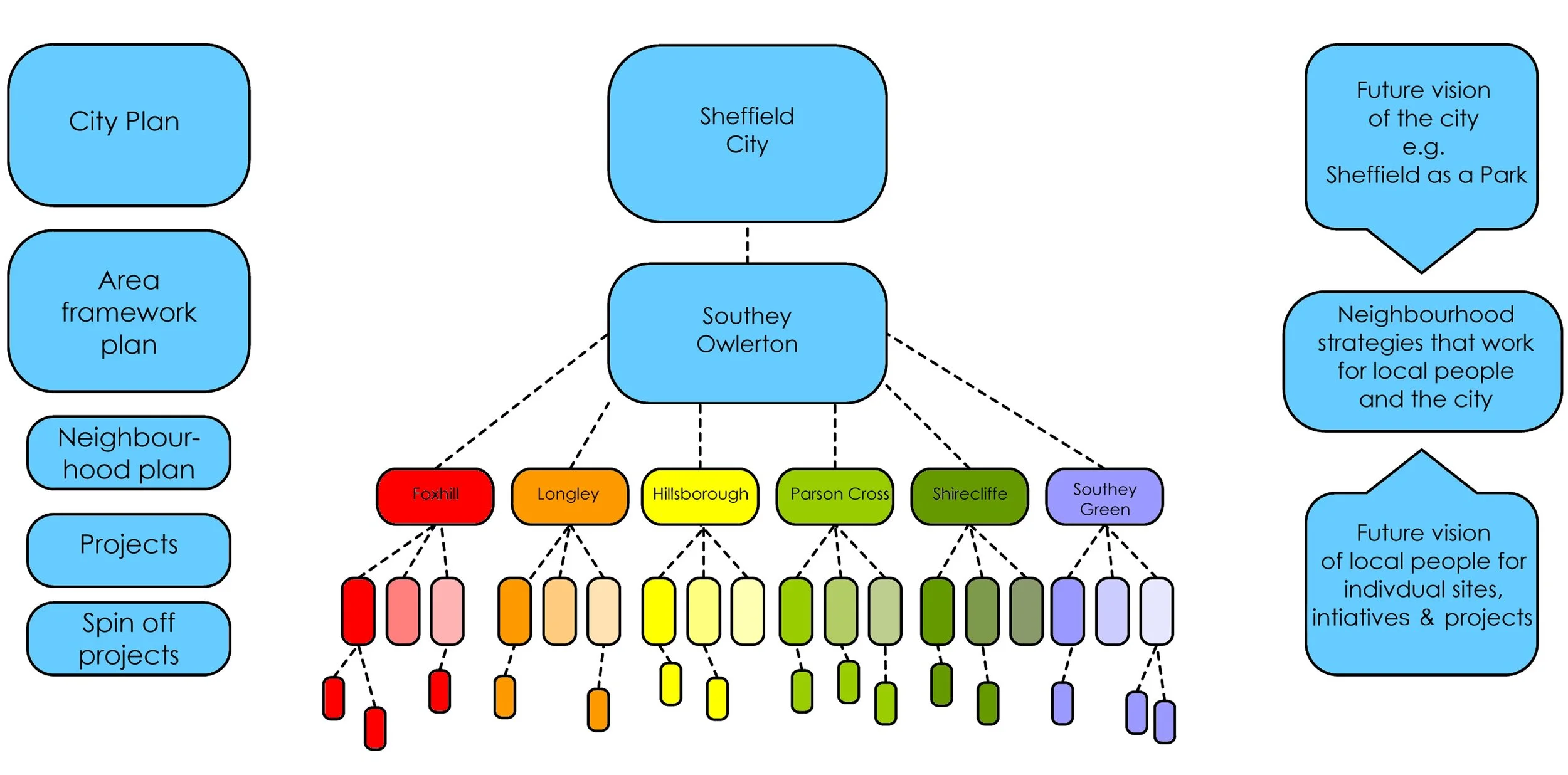

The plans connected across different spatial scales: grass roots, neighbourhood and city.

The six neighbourhood plans were supplemented with a regeneration framework for the area as a whole. The documents embraced social, environmental and economic sustainability and were extensively illustrated with plans, diagrams and precedent images.

moving between the individual, neighbourhood and city scale generated a dynamic "top-down, bottom-up" narrative that keyed the area into a wider narrative for the city.

Some themes were specific to a neighbourhood, others were shared and others were characteristic of Sheffield at the city scale.

This was crucial in connecting an isolated part of the city to the rest, changing people's perception of where they lived; and also in changing how the rest of the city saw the area. In particular, it helped validate the new masterplan, renamed the Southey Owlerton Neighbourhood Strategies and was formally adopted by the council.

#5 Facilitative leadership & effective multi-agency working

Facilitative leadership on the part of the programme team kept the process moving without compromising on co-design. The SOAR team led and oversaw the process, facilitating the engagement of the participants.

The SOAR team was a band of brilliant people who did amazing work to develop the partnership into a community anchor organisation, a role it retains today under the leadership of Ian Drayton, who at this time was a resident, activist and chair of the SOAR Board.

SOAR was very lucky to have two amazing team members to lead this process. Chloe Aspinwall and Sarah Smith supported the community groups and acted as the “glue” in the whole process, which was necessarily complex and involved many stakeholders, relationships, ideas and projects.

chloe aspinwall (right) supported the six neighbourhood groups.

sarah smith hosting a workshop.

The neighbourhood groups met frequently, especially in the build up to events and to develop ideas and plans. A resident representative and worker from each neighbourhood met monthly as part of a steering group for the process.

A team of council staff from every directorate met weekly to review progress and share reflections, as did the team of consultants. A more council senior team, again with a representative from each directorate, met monthly.

Effective multi-agency working (public, private and voluntary sectors) supported the process and paved the way to delivery of key projects, because people “owned” the proposals and wanted to see them happen.

It was very meeting and labour intensive! All the conversations were face to face and required a huge commitment from all participants. It took two years, which at the time seemed very quick, but the amount of work involved was phenomenal.

It worked

The experiment worked - the plans were approved by SOAR and the neighbourhood groups and were also endorsed by the Council and the Local Strategic Partnership - they worked at a grass roots and at a city scale.

The new plans set the priorities for the rest of the regeneration funding and led to a whole set of demonstration projects: housing, parks, community buildings, neighbourhood centres.

The plans have endured: they are still in force today 20 years later.

And the methodology proved to be resilient: when we came to plan the adjacent neighbourhoods, our friends at Fluid were able to replicate the process, the thinking and the notation.

What needs to change today?

So what’s changed in 20 years? And what should we do differently now?

The SOAR neighbourhoods were adjacent to each other and together formed a bigger entity. South Yorkshire Housing Association’s estates are spread across a wide geography and may not feel connected.

I recently came across Lisbon’s Bip/Zip model of neighbourhood renewal which covers a number of micro-neighbourhoods across the city. I felt immediately the parallels with our work at South Yorkshire Housing Association which spans myriad micro-neighbourhoods across Sheffield City Region.

The Lisbon model started with a mapping exercise to identify the different characteristics of the neighbourhoods and which ones to prioritise. This feels like a useful starting point for us, given the number of estates we manage. (This stage had been completed at SOAR as part of securing the regeneration funds.)

The Lisbon model has five elements:

A data-led approach to mapping, based on detailed socio-economic-spatial indicators that identify priority neighbourhoods.

Qualitative data generated from grass roots surveys of, and conversations with, local people to identify what needs to change in those neighbourhoods.

Direct support of community groups in those neighbourhoods through grants - a start-up fund for social initiatives - and small projects.

Ongoing improvement of the neighbourhood through local multi-agency partnerships.

Collaboration between neighbourhoods through a digital platform.

co:create, our coproduction consultancy asks participants to identify where they live using digital maps - it allows them to reach more people and is much easier than lugging heavy models around! people can add their pins remotely and you can collect other sorts of data, in this case the age of participants. image: co:create

I also felt immediately the parallels with the Neighbourhood Strategies - but with some key differences:

Availability of data - the ability to access, manipulate and present vast quantities of data at a micro scale has been transformed in the last 20 years.

Digital conversations - we relied heavily on talking to local people at meetings and events and this of necessity limited the number and type of people we could reach; engaging with people digitally opens up the opportunity to canvas ideas from a much broader cross-section of the community.

A digital ecosystem - we brought people together from different neighbourhoods in groups and governance structures; a digital platform allows the possibility for informal and real-time sharing of ideas and experiences across neighbourhoods.

Adding data and digital to the mix will allow us to:

Build rapidly a picture of the needs of the neighbourhood and match that with local people’s thoughts.

Engage with people through a range of channels including our website and social media platforms.

Use our website to develop an ecosystem of practice across our neighbourhoods where our customers can share and learn from each other’s ideas.

Screen grab from our South Yorkshire Housing Association website.

What next?

The situation with our estates is completely different from SOAR’s: the neighbourhoods are small (up to 200 homes) and dispersed, they are in good shape and the conversation is about long-term stewardship and small-scale, continuous improvement, rather than major change through big regeneration funds.

But there is useful learning to take from the SOAR work as we build a picture of what to improve:

Start with local people’s stories and experience of their place, and kickstart action with small projects and micro grants.

Recruit excellent designers to visualise and help implement the ideas.

Make use of creative tools to open up dialogue.

Make connections between places and across the area as a whole.

Facilitate the process carefully and engage a range of agencies to support the work long-term.

So we plan to adopt the Lisbon framework and build on the experience of Well Rotherham and the Neighbourhoods Strategies.

We have the basis of our model and will start to test it later this year. Watch this space…

You can find out more about Well Rotherham on our website.

If you’re interested in exploring co-production, why not get in touch with Co:Create at wearecocreate.com? They specialise in making the process accessible and engaging for organisations, focused on practical change that is rooted in community development methods and principles.