A green & blue space system for Sheffield: a brilliant demonstrator for our new City Goals

Celebrating 20 years of green space projects in north and south Sheffield

In memory of Lynn Kinnear 1960-2024

Project team - Southey Owlerton Area Regeneration (SOAR) parks:

Community client - SOAR Board and Neighbourhood Forums in Foxhill, Longley, Parson Cross, Shirecliffe and Southey

Community engagement - SOAR team, Parks & Woodlands team, Sheffield City Council, Sheffield Wildlife Trust

Liveability - North Sheffield Regeneration Team, Sheffield City Council with support from Sue France, The Green Estate

Landscape design:

Andrew Grant, Grant Associates

Eelco Hooftman, GROSS MAX

Lynn Kinnear, Kinnear Landscape Architects

Rachel Devine & Neil Swanson, Landscape Projects

Sheffield is rightly proud of its extensive green and blue infrastructure.

Its topography - seven hills and five river valleys - along with its woodlands were the raw ingredients that fuelled the cutlery industry, which later developed into large-scale steel production in the east end of the city. The city’s natural assets are the foundation for its identity.

Today with 60% of the city given over to green space and some 4.5m trees, it can lay claim to being the greenest city in England, although the disparity between the north-east and south-west of the city is marked, in terms of the quality and quantity of green space and trees, as it is in so many other ways.

sheffield’s green and blue infrastructure image prue chiles

But is the city really getting the most out of this infrastructure? And how would treating it as a system help?

From green spaces to a green & blue space system

Frederick Law Olmsted, the “father of landscape architecture” in the United States, was the first person to recognise that a linked system of parks and open spaces conferred significant benefits for urban areas.

His first, and possibly most famous, major commission in 1857 was for the creation of Central Park in New York City and he completed many other public parks during his career. But it was in subsequent projects like the Emerald Necklace in Boston (from 1878) and the park system in Louisville, Kentucky (from 1891) where he realised his ambition of achieving a coordinated system of public parks linked by green parkways and rivers.

olmsted’s emerald necklace park system in boston

the muddy river was dredged into a stream that linked jamaica pond to the charles river. parks were added to the west and south, creating a linear park system that still exists today.

cherokee park, louisville

olmsted’s parks offered access to nature for urban communities characterised by great use of topography, welcoming routes and local materials & plant species.

the park system in louisville, kentucky, one of only four completed olmsted park systems.

initially the plan was for six parkways linked to three major parks. a further fifteen smaller parks were added as neighbourhoods developed. the system took fifty years to complete.

These park systems not only provided access for everyone to public green space, with all the consequent health and other benefits, but also connected people and wildlife via walks and paths to naturalistic landscapes, managed waterways for flood protection and promoted nature conservation. They became embedded in the structure of the city and are still in place today.

Influenced by the English garden and landscape tradition, his designs were rooted in the natural qualities of a place and emphasised usefulness over decoration.

Stuttgart in Germany, a sister steel city to Sheffield, shares some of its physical character. Sitting in a basin between two river valleys, heat inversions were frequent and exacerbated by industry. Like Sheffield it was also heavily bombed in the war.

As part of its post-war reconstruction it took the opportunity to create a park system that would mitigate the problem of heat inversions: a network of suburban parks, linked by urban pathways with safe road crossings, was created on ridges projecting into the city. Air temperatures over the vegetation were lowered and the cool air dropped into the city below. (Importantly this initiative has been supported by planning policy that prevents building on the hills and in ventilation corridors, despite development pressure.) As in parts of Sheffield, people can now walk from the city centre via a continuous footpath system through these parks to woodlands and countryside.

green ventilation corridors in stuttgart, germany

extensive tree planting linking a network of parks on the high ground above the city mitigates the problem of heat inversions.

a park in stuttgart

the parks are beautifully maintained for people’s safety and enjoyment.

the green space system in stuttgart

the landscape framework was conceived as a totality and wraps round the city in a u-shape.

green corridors in stuttgart

wooded ridges and green spaces form a herringbone network on the ridges above the city linking the city to countryside.

The landscape was conceived as a totality, carried out with imagination down to the last detail and beautifully maintained for people’s safety and enjoyment. The result is that 60% of the urban area is green space configured in a U-shape across the city, in a diverse range of multifunctional spaces and habitats, from formal parks to forest. The green space system works for people, supports active travel, promotes bio-diversity and mitigates urban heating.

Green & blue space systems move us beyond the individual and static interventions of a green space plan to a dynamic, interconnected set of resources that can start to address the many and complex challenges we face: soil, air & water quality, bio diversity, food production, carbon sequestration, flood protection, temperature control, energy, physical and mental health, local jobs and businesses, social connection, community participation - you name it, green & blue space systems have a role to play!

And we can start to consider whether the key features - resilience, self-organisation and hierarchy - that ensure systems function well, are in place.

In the case of green spaces, for example, does the system allow for resilience and adaptation as well as productivity? Can changes that enrich spaces be locally-led? Can the whole equal more than the sum of the parts? Can we ensure a more equitable approach to green space across the city? Can we, over time, deliver greater benefits for people, place and planet from our green spaces with less or different money and resources?

“We need to see green space as part of our life support system. It helps deliver food, water & oxygen and provides spatial and ecological experiences that enrich our life, our health and our mental wellbeing.”

Why a green & blue space system would make a brilliant demonstrator for Sheffield

emmaus primary school at the green estate

The newly developed City Goals point towards 6 stories that Sheffield wants to be able to tell in 2035:

#A creative & entrepreneurial Sheffield

#A green and resilient Sheffield

#A Sheffield of thriving communities

#A connected Sheffield

#A caring & safe Sheffield

#A Sheffield for all generations

Demonstrator projects are one way to show what the City Goals look like in practice, by testing how different infrastructure and governance arrangements can meet inter-twined economic, environmental and social challenges.

They are effective mechanisms for forging partnerships between public, private and (especially) community sectors, developing new ways of working together, learning by doing, and generating visible results on the ground.

Demonstrator projects need to be significant enough to be relevant, replicable and transferable. Ideally they will demonstrate impact on as many as possible of the City Goals. They also need to involve all the key stakeholders so that there is support and buy-in to apply the models to other parts of the city.

Piloting a green & blue space system in one part of the city would make a brilliant demonstrator because:

#1 It could show impact on most, if not all, of the City Goals.

#2 Thinking about systems helps us understand how to address structural problems and make real change.

#3 We have a great base to start with - good practice and learning to build on in the four quadrants of the city and the city centre

This blog reflects on the potential for a green & blue space system across the whole city and proposes that the work of the Green Estate in Manor would make an excellent demonstrator (full disclosure - I recently became a trustee!)

A city-wide green & blue space system

One of the challenges of demonstrator projects is that most people don’t want to replicate the experience and learning of others: they want to develop their own solutions, solutions that are relevant to their unique location.

A city-wide system does not mean adopting a uniform approach across the city.

diagram of sheffield based on a simplified contour map - andrew grant

the topography of the city creates four distinct landscape quadrants that converge on the city centre.

When we were working on the Regeneration Framework for Southey Owlerton in north Sheffield, Andrew Grant, Director of Grant Associates, was part of the creative team. After working alongside local people and multi-agency stakeholders for some weeks, he presented his ideas.

The occasion was memorable, not just because of his hand-drawn diagrams on overhead projector acetates (hard to believe that technology was still in use in the 21st century!) - he inspired us with his vision for the area including the 5 Big Ideas and the framework diagrams which are still in use 20 years later (part of the Southey Owlerton Neighbourhood Strategies).

One of the diagrams, based on a simplified contour map of the city, indicated four quadrants, connected by the city centre. Each of those quadrants has a distinct topography which means that each has a different starting point in terms of green space:

#The knolls of the north - parks and green areas spaced out across the different neighbourhoods

#The flood plain of the east - dominated by the river Don

#The gentle undulations of the south - larger swathes of green space within residential areas

#The incised valleys of the west - rivers and woodland that thread from the Peak District through Victorian suburbs to the city centre

#The hill that forms the city centre - bounded by the river Sheaf to the south.

Each of these areas has great experience and learning to contribute to a green & blue space system across the city.

view of sheffield showing the valleys converging on the city centre

The reason for proposing the Green Estate as a demonstrator is that it has in place the key conditions for success:

#1 The green spaces it manages have been conceived as a totality, moving over time from a regeneration agenda towards adaptation and resilience

#2 Imaginative design executed over many years is rooted in the place

#3 Fantastic management & maintenance, marked by multiple Green Flag awards, go way beyond “normal” grounds maintenance

#4 Local people, community groups and multi-agency stakeholders are actively engaged

#5 It has the potential for effective coordination and monitoring of resources across a significant area.

the green estate

a green space system across manor, including manor oaks farm, the arena & discovery centre, manor lodge and manor fields park. 42ha of derelict land converted to a sustainable and productive landscape.

Learning from each other

If demonstrators are to be scaled successfully, they need to work collaboratively with other locations in the city, learning from each other on a reciprocal basis. What can other parts of the city tell us?

Below I compare my direct experience in north and south Sheffield and signpost to case studies in the rest of the city.

Place-making in north Sheffield

the framework diagram for southey Owlerton

green spaces in each of the five neighbourhoods linked by footpaths form a green space system across the area.

In the early 2000s (20 years ago!) a major programme of investment took place in parks in the Southey Owlerton area of the city.

Southey Owlerton Area Regeneration (SOAR) had been awarded some £30m of public funding, of which approximately £5m was allocated to green spaces because:

#Local people had prioritised green spaces as an area for investment - most of the parks were little more than areas of mown grass, created as part of the inter-war council estate, but fantastic views, the extent of green space and contact with nature were seen as positive eatures of living in the area;

#High quality public space was seen to be an important way to change perceptions of the area and to encourage development of new homes as part of the regeneration process;

#The regeneration framework, developed with the community and a range of stakeholders, proposed a park for each neighbourhood connected by footpaths/cycleways to form a green space system - sites were chosen that formed the heart of a neighbourhood.

The design of the parks was driven by a number of factors including:

#A commitment that local people would set the brief, choose the designers and be actively engaged throughout the design, implementation and maintenance process

#A desire to create a distinct identity for each of the five neighbourhoods and for the area as a whole

#Provision of facilities that would improve the day to day quality of life for existing and new residents - the need for immediate impact

#A longer term focus on the potential for a green space system across an area that formed one tenth of the city

Involvement of local people in the design process

People who lived in the area worked with a range of stakeholders to develop the plans for their neighbourhood parks. Neighbourhood representatives also worked collectively across Southey Owlerton to create a network of parks that would serve the whole area.

developing the project brief

CAbe (the commission for architecture & the built environment) sponsored a design panel of enablers to work with local residents in each neighbourhood to develop the brief for each site.

appointing the design teams

cabe trained the neighbourhood groups in how to assess tenders and manage design teams. the neighbourhoods tendered collectively for the design of all the parks to attract more interest - over 50 firms applied (!) and their proposals were scored in detail by representatives from each park. shortlisted firms were then interviewed by a panel of residents and council staff who chose the design team they felt was right for their park.

overseeing the design process

each group worked with the design team it had appointed to develop and refine the proposals for each site.

design workshops

the designers worked with specialist groups on specific parts of the park - here a group of young people are advising on a skate park.

design workshops

the designers worked with as many age groups as possible to ensure the parks would have something for everyone.

Distinctive neighbourhoods

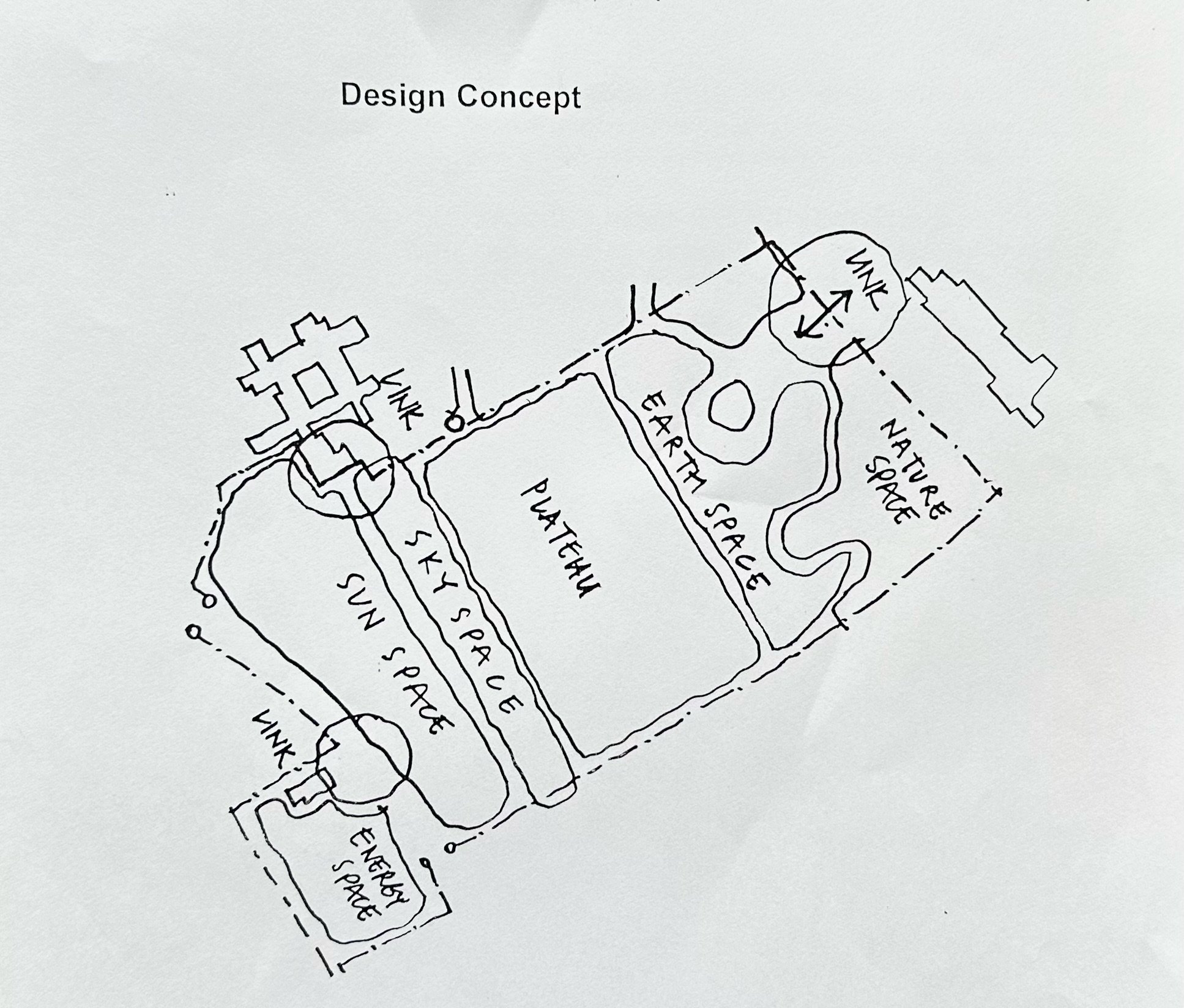

CONCEPT for colley park, parson cross, grant associates

the design proposed a sky space on the high ground with an earth space in the hollow.

One of the challenges for Southey Owlerton was that all the neighbourhoods merged into each other and looked the same (even though they were clearly separate communities). This was because the inter war housing had been laid out uniformly across the area, without taking account of differences in topography, aspect and vegetation patterns - whereas sunny hilltops, characterised by grassland and long views, actually felt very different from the secluded spaces and shady woodland on the lower slopes. In addition, each neighbourhood lacked a clear focal point or “centre”.

The regeneration programme therefore funded projects in each neighbourhood that would create a distinct centre or “heart”, including a community building, a public space connected to shops & other facilities and a park.

Emphasis was given to the design of these projects - so that they stood out - and a different design language was developed for schemes on the tops of the hills - the sky space - and schemes on the lower slopes - the earth space - so that the neighbourhoods would feel more distinctive.

The terms sky space and earth space originated in Andrew Grant’s plan for Colley Park, which included an elevated, sunny ridge to the west and a shadier hollow to the east.

sky space

an urban design language with tall features oriented to the views and visible from afar, metallic & light coloured materials that shine in the sun and move in the wind, grasses & silver foliage, accents of yellow, scarlet & orange.

earth space

a quieter semi-rural design language wth secluded spaces, earthier elements like play boulders, timber seats and stone walls, naturalistic planting, warm and earthy colours.

Sky space parks

plan for colley park, grant associates

the sky space is linear, man-made and brightly coloured in contrast to the earth space which is organic and naturalistic.

detail of the sky space, colley Park, grant associates

shiny & colourful play equipment and lighting push up into the sky.

wolfe road park, foxhill, landscape projects

use of the slope, sky blue play surface and a colourful shelter

sketch proposal for cookson park, southey, kinnear landscape architects

sky blue and grey skate park set in grassland and open to the skies, silvery blossom

detail of the shelter at wolfe road park, landscape projects

metalwork in sunny colours

detail of the play wall, cookson park, kinnear landscape architects

sky blue and grey wallpaper design

Earth space parks

parson cross park & tongue gutter, kinnear landscape architects

the concept for this massive 26 ha site, which had been converted to potato fields during the war, was to re-introduce a productive/semi-rural character through meadows, a path along the stream, drystone walls, farm gates, stiles and potentially grazing animals.

busk meadow park, shirecliffe, GROSS MAx

the masterplan linked existing woodland and meadow to new facilities linked by a red path.

busk meadow park, gross max

the red path with meadow and woodland behind. stone gabions framed naturalistic birch trees and beds for food growing.

busk meadow park, gross max

a section showing gabion walls & multi-stemmed birch trees

longley park, longley, landscape projects

proposed improvements to this established park included new paths & stone features at key junctions, opening up the stream, a marsh garden and new woodland planting.

four greens, longley, landsdcape projects

the four greens at the heart of longley were each given a separate character. on this one, stone walls and earth banks create elliptical planters around the existing trees.

four greens, landscape projects

here, informal paths wind through naturalistic meadows and glades.

four greens, landscape projects

stone and timber for informal seating and play

longley park, landscape projects

woodland and meadow frame the spaces in the park.

Improved facilities

The emphasis was on providing much-needed facilities for children and young people in an attractive setting for adults. The aim was to provide basic facilities in each neighbourhood and more specialist facilities that could be shared across Southey Owlerton. The parks worked as a set.

sky space, colley park

play equipment for a range of ages alongside a multi use games area

wolfe road park, foxhill, landscape projects

the play area before and after investment

cookson park, southey, kinnear landscape architects

play area, climbing and play walls

cookson park, kinnear landscape architects

the cycle speedway, a specialist facility designed with a local club that brought people from beyond the area

cookson park, kinnear landscape architects

the skate park, designed with a local bmx and skater group to serve the whole southey owlerton area and beyond

cookson park, kinnear landscape architects

the opening event for the park

busk. meadow park, gross max

proposal for an enclosed kickabout on what had been a waterlogged, unplayable field

busk meadow park, gross max

a new wildlife area: wetland, boardwalk and woodland walk

Towards a green space system

longley park, landscape projects

the designs enhanced the natural topography and habitats.

maggie’s field, southey

naturalistic spaces included informal play.

Although the focus was primarily on providing facilities that would have immediate impact, the designs also incorporated features that would be permanent by enhancing the natural topography and habitats of the area and making the most of the views. Some more naturalistic spaces were also improved, to help piece together a connected web of green space across the area.

However the long-term stewardship arrangements and business plan needed to achieve a successful green space system were not realised.

Southey Owlerton bid successfully to the government’s Liveability programme (2004-06). This aimed to establish a new way of managing and maintaining public open space via a cross-sector “client” partnership that included the three different landowners within the council alongside the voluntary sector and local people. Up front capital funding (the carrot) was provided for physical improvements alongside revenue funding to test a different maintenance model.

Most of the land in Southey Owlerton was in the ownership of the council, but the maintenance was carried out by different service providers, both public and private. Residents were frustrated that basic standards of clean, green and safe spaces were compromised by different contractors working to different systems and standards, even where their land was immediately adjacent. The aim was to achieve a more coherent and consistent approach through a single client team that would work on behalf of the broad coalition of clients in the partnership to agree management plans, set and monitor consistent and appropriate maintenance standards and decide how to prioritise resources including a rapid response service and involvement of community groups.

Despite a collaborative process over several years, co-location of the key maintenance teams and testing different work arrangements, the changes were not achieved. In the end we couldn’t successfully overcome the challenges of different terms and conditions across the providers and competing/limited resources. An independent evaluation by the University of Sheffield concluded that although the governance structure was sound, buy-in at all levels in the partnership and a long term programme were necessary to achieve management and maintenance that could get beyond the basics to effective stewardship or place-keeping.

Reflections

The parks were conceived as a totality and imaginatively designed with the engagement of citizens and agencies. But the programme failed to deliver on the high standards of management & maintenance that are essential to a green space system.

It was always clear that more revenue would be needed to achieve the necessary management & maintenance and a business plan was part of the project. We weren’t to know that a housing market crash and a long period of austerity were just around the corner.

On the one hand, with hindsight the green space programme feels ludicrously ambitious especially given the short timescale - we had four years to deliver the programme (and we know from Louisville and Stuttgart that this work takes decades!). But on the other hand, the ambition to achieve one decent park per neighbourhood, a set of facilities for a population of 50,000 and a green & clean public realm feels pretty modest, especially given the inequity in green space quality across the city.

We didn’t achieve the green space system we hoped to, but luckily another organisation in the south of the city was testing a different model with more success.

From place-making & place-keeping to adaptation & resilience in south Sheffield

Place-making & place-keeping

manor oaks farm house before and after restoration, the green estate

a derelict building has been converted to a wedding & hospitality venue as part of an income generating strategy.

Meanwhile, in parallel with the work in Southey Owlerton, the Green Estate was busy developing a green space system based on a very different model. Here the focus was on long-term landscape management and maintenance rather than capital investment.

Sue France, founder and former Chief Executive of the Green Estate, started by assembling the revenue funding needed to pay for a small team to work with residents on improvements to the area, as part of the wider regeneration programme. Employing people-focused rangers was a key feature of her approach.

Manor fields park before, the green estate

large tracts of undesigned and unmanaged green space across the neighbourhood have been transformed…

From her start in 1999, initially employed by the Sheffield Wildlife Trust, she also worked on securing revenue funding for long term management & maintenance; she recognised that it would take 25 years - a generation - to make the change. The plan was to generate sufficient funds from: transfer of income-generating assets; new enterprise; endowments e.g. for Sustainable Drainage Schemes (SuDS), ground rents and service charges associated with new housing developments; and procurement by the council of long term (e.g. 25-year) contracts for grounds maintenance.

The starting point, in consultation with the community, was to investigate every piece of green space in the Manor area, regardless of ownership, and identify every opportunity for partnership, improvement and income generation. A set of management plans were developed for the sites (still somewhere in the archive!) and numerous business ideas explored from lavender farms to adventure play to donkey sanctuaries and cheese production.

Manor fields park after, the green estate

….into beautiful & well-used places, designed and managed for people and nature..

Single Regeneration Budget and European funding was secured for 4 years which allowed the core team to expand from 2 to 18 people. Improvements were made to three pocket parks and to Manor Fields (all sites still maintained today by the Green Estate). Further funding helped secure the Manor Lodge site: leases with the council and the Duke of Norfolk were negotiated and private interests acquired. In total some £5m was invested in securing and restoring the assets.

Spaces were designed with complexity and structure to benefit people and wildlife. The team experimented with low-input solutions - meadows and different substrates - and made sure that basic requirements like fencing, gabions and play equipment were imaginatively designed, not purely functional. Management & maintenance arrangements were tested following the same principles as the Liveability programme in north Sheffield, where Sue had generously acted as advisor and supporter. A key component was having rangers on the ground to respond to residents’ ideas and feedback and to keep adapting the plans.

20 years on, this is a remarkable success story: the quality of the green space speaks for itself; Manor Fields has been recognised for the 11th time by a Green Flag award; Pictorial Meadows is an established business with a national and international reach; the Green Estate was in 2023 awarded the King’s Award for Enterprise in the Sustainable Development category; over 20,000 visitors attend the site each year; and with a turnover of £3m and employing over 70 people it is a significant enterprise in the city.

I love this quote from a fellow trustee at the Green Estate. It reminds me of how green spaces are the backdrop for so much of our everyday quality of life, our connections with other people, nature and the place where we live. For me it epitomises what the Green Estate has achieved over the last 20 years.

“As a little girl growing up in S2, green space meant…

Seeing tadpoles in the pond on eastern avenue and sitting with my uncle Jack as he fished. Going to Sunday league football with my grandad on the local playing fields. Playing rounders on the school field with friends in the heat of the school holidays. Watching the lilac tree blossom and the peonies bloom in my nan’s garden. Plus picking the best rhubarb from the patch they had and eating it straight away. Walking across green space that connected my grandparents’ house on the Arbourthone with my aunts and uncles on Manor Lane. And walking down to Norfolk Park across fields to visit the fair.

S2 was always beautiful to me.”

Towards adaptation and resilience

pictorial meadows at Manor oaks farm, the green estate

showcase for an adaptive and resilient urban landscape.

For Roz Davies, the Chief Executive of the Green Estate since April 2022, place-making and place-keeping is only part of the story. Her vision is to showcase on the Manor how to grow green and urban resilient places for people and nature to thrive. To provide a living example of how local services, local land and local research & expertise can make places, communities and businesses less vulnerable to financial and climate insecurity.

The Green Estate has a track record in developing innovative solutions, grounded in what is needed within its local community, and exporting them to the city and beyond. Pictorial Meadows is a wildflower seed and turf business, developed with the University of Sheffield, originally to improve cleared housing sites and green spaces in the Manor (a brilliant landscape treatment for our time). Green waste recycling, development of special “soils” and expertise in Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) have spawned other businesses that now operate nationally. Grey to Green in Sheffield city centre is just one example of the Green Estate’s wider influence. A massive urban flood resilience scheme in Mansfield, that aims to capture and clean 58,000m3 of surface water through rain gardens, bio swales and basins, whilst improving green spaces and bio diversity for a community of 90,000 people, is another.

Manor fields park, the green estate

sustainable drainage system under construction, now greened. the scheme serves the adjacent housing development, saves the developers. money and earns income for green estate.

manor oaks, the green estate

commercial manufacture of specialist soils for suds and urban resilience projects

flood resilience at scale in mansfield

the green estate is contracted to provide the specialist soils and horticultural expertise.

Roz would like to take this further by offering other hopeful and practical solutions to help build resilience into urban places communities and businesses in a way that is good for people and nature.

Her vision is of the Green Estate becoming an urban resilience centre - not a single building or function but a living, breathing ecosystem of activity that tackles the climate and biodiversity crises whilst bringing joy to people and creating volunteering, employment and business opportunities. A potent mix of ideas, partnership and practical delivery including food production, wildlife, cultural heritage, recycling, peat free compost, new types of soil and supporting community enterprises - all set in beautiful landscapes.

ranger jayne and volunteers at the green ESTATE

rangers are a key ingredient of the green estate model.

bonfire night event, manor fields

joyful events, day and night, bring people together.

the fishing pond, manor fields

something for all ages

repairing the boardwalk, manor fields

volunteers have a chance to make a tangible difference in their community.

food growing with volunteers and training, manor oaks

42 ha of land provides plenty of opportunities for food growing!

mini allotments, manor oaks

supporting a local food system is akey priority for green estate.

cultural heritage, manor lodge

the scheduled ancient monument is an ideal place to celebrate the stories and history of the manor.

pictorial meadows, manor oaks

a local solution for TRANSFORMING derelict land to beautiful and biodiverse medows has spawned an international business which helps sustain the green estate’s work in s2.

Reflections

The Green Estate, whilst fantastic, is not an unqualified success - yet.

Sue France’s original vision of generating income from its own assets to create a self-financing green space system has only been partially realised. For example, the ownership of Manor Fields wasn’t transferred to the Green Estate nor was a 25-year lease secured, although the council has renewed annually its service level agreement. And commercial income via Pictorial Meadows is generated mainly from places outside the city.

And whilst the maintenance of Green Estate’s assets is exemplary, it hasn’t been able to take on responsibility for much additional land. An exception is Woodthorpe where the Sheffield Housing Company, through its service charge, has funded maintenance of a landscape designed for people and nature (though the money doesn’t sadly run to a ranger).

Could this model be extended to pilot what a mini-green space system across different ownerships would look like? We think it could.

What if we…..

#Dust off the plans for all the green space in the Manor area, including gardens and street trees, and look afresh at opportunities to create productive landscapes for people and nature

#Develop a client partnership to represent all interests (landowners, community groups etc) in the area, supported by the council as citywide facilitator

#Use the green space expertise within the Green Estate (a mix of community rangers, horticulture, landscape design, management & maintenance) to develop simple management plans for each site and the whole, and to oversee work on the ground on behalf of the client partnership

#Capture data to evidence the impact and value of this work to the partners and investors

# Look at new sources of finance to support the investment needed - such as Biodiversity Net Gain, further SuDS schemes, private investment for carbon reduction returns, public investment to capture health and other benefits etc.

Let’s build on the success of the Green Estate’s model to learn more about the potential for a green & blue space system in the city.

Could this be the start of the UK’s first Urban National Park?

Natural resource management in west Sheffield

Every part of the city has the scope to integrate our blue and green infrastructure, but nowhere more so than the west of the city where the Upper Don, Loxley, Rivelin, Porter and Sheaf valleys link the city centre to the Peak District National Park.

Incised river valleys with steep slopes that can’t be built on, have created fingers of woodland, meadow and industrial heritage stretching from the countryside to the city and making it possible to walk from the city centre to the Peak District alongside rivers via a network of paths and green spaces, just as Olmsted envisaged in his park systems.

The Upper Don Trail Trust, the Rivelin Valley Conservation Group and Friends of Loxley Valley and Porter Valley are all active in improving each corridor.

But what if these groups, the council and the National Trust could work together on a wider plan for the valleys, moors, farmland and forestry under their joint control to create a “natural enterprise zone”? A system of activities and businesses that support adventure, tourism and a healthy way of life; productive land (food and timber); and a carbon bank and flood resilience to help tackle climate change.

A similar vision for Parkwood Springs in the Upper Don was proposed by the community in work facilitated by Prue Chiles and Sarah Smith some 20 years ago. It’s great to see work start at Parkwood Springs, an area as big as the city centre, with the potential for an amazing piece of inner city “countryside”.

rivelin valley trail image outdoor sheffield

woodland, water and industrial heritage link the city centre to the peak district.

vision for parkwood springs image prue chiles

adventure, production and a carbon bank

Urban ecology in east Sheffield

The Five Weirs Walk Trust and the Blue Loop have done a brilliant job at creating walking and cycling routes along the Lower Don and the Tinsley Canal.

What if all the corridors in the Lower Don Valley - river, canal, rail and road - were enhanced to provide the UK’s “greenest” investment zone? This could be a great companion to a “natural enterprise zone” in the west of the city.

the five weirs walk on the river don, east sheffield image prue chiles

the lower don in its industrial setting could be the centre of a green investment zone.

the five weirs walk, east sheffield, image prue chiles

the blue loop creates a round walk and cycle route along the river and the canal.

From grey to green in the city centre

Sheffield’s Grey to Green scheme, which is steadily expanding, is inspirational and becoming a hallmark of the city centre. Combining flood protection, water filtering and beautiful landscapes, it’s a brilliant example of integrating blue and green infrastructure.

Combined with the new Pounds Park and other green spaces, Sheffield can claim to have the greenest city centre in the UK.

New work to open up culverted sections of river will strengthen the connection between the city centre and its surroundings and start to link the integrated blue and green infrastructure across the whole green space system.

pounds park image heart of the city

a new park in sheffield city centre

grey to green image nigel dunnett

sustainable urban drainage combined with beautiful planting have transformed grey infrastructure to green and blue.

Conclusion

All these examples show how managing our green and blue infrastructure as a system could have greater impact for people, place and planet: local people and groups drive change at the neighbourhood level, democratic deployment of resources provides greater equity across the city, there are new opportunities to generate investment, we create a landscape that is beautiful, joyful and resilient, the whole is more than the sum of the parts.